Dependency Injection in Vue.js Applications

I often wonder how to decouple certain parts of an application best. At first, this seems pretty straightforward in the context of Vue.js applications. You have components and components pass down properties and emit events; that’s it. Right? Yeah, kind of. But also kind of not. Soon there will be the need to access global state or retrieve data from an external resource via an API. If we don’t be careful how we tackle these challenges, there will be the time when we realize that our components, which we planned to be nicely decoupled, use many external dependencies and are anything but decoupled.

In this article, we take a look at what patterns exist in Vue.js applications to provide dependencies to components. We examine the advantages and disadvantages of each approach and what alternatives there are to each. Also, we learn that certain methods are very well suited for particular use cases but not so well for others. After reading this article, you should have enough tools in your utility belt to decide whether a hammer or a Phillips screwdriver is a better choice for a specific use case.

Table of Contents

- Importing modules

- Decoupled component composition

- Plugins

- Provide / inject

- Functional component factories

- Injecting global state

- Third party tools

Importing modules

Let’s start with the first method of “injecting” functionality into a Vue.js component: module imports. Although one might argue that this is the complete opposite of dependency injection, I use the literal sense of the words. Even if you don’t agree with me calling this a form of dependency injection, I think it’s still worth taking a closer look at the pros and cons of this practice.

<!-- components/LoginButton.vue -->

<template>

<button class="LoginButton" @click="login">Login</button>

</template>

<script>

// Tight coupling, not recommended.

import { login } from "../services/user";

export default {

// ...

methods: {

async login() {

this.success = await login();

},

},

// ...

};

</script>There are a few things that are wrong with this example above. First of all the name: LoginButton. We could make it much more reusable by calling it SubmitButton instead. The main problem, however, is the tight coupling with the login() method of the user service. By decoupling this component from this hard-coded dependency, we can make it much more useful.

<!-- components/LoginForm.vue -->

<template>

<div class="LoginForm">

<BaseInput />

<-- ... -->

<BaseButton @click="$emit('submit', data)"> Submit </BaseButton>

</div>

</template>

<script>

// Okay usage of imports.

import BaseInput from "./BaseInput.vue";

import BaseButton from "./BaseButton.vue";

// ...

</script>In the above example we also use imports but this time we use it to import base components which are the basic building blocks of our application. Think of them as HTML elements on steroids. You might even consider to globally register such components (although I’m personally not a fan of this practice).

<!-- components/UserFormContainer.vue -->

<template>

<UserForm @submit="login" />

</template>

<script>

// Okay usage of imports.

import { login } from "../services/user";

import UserForm from "./UserForm.vue";

export default {

name: "UserFormContainer",

// ...

methods: {

async login(data) {

this.success = await login(data);

},

},

// ...

};

</script>Here you can see a container component. While it is still technically the case that we closely couple this component with the user service by importing it directly, we allow ourselves to do so in container components. There has to be some place(s) in our application where the coupling happens. Think of container components as poor mans IoC containers. These container components are deliberately tailored to a very specific use case.

Recommendation: try to only use import in container components or for importing base components. Use sparingly otherwise.

Decoupled component composition

Although it is usually not called this way, slots in Vue.js are actually an implementation of the IoC pattern. Let’s take a look at the following two code examples to see what I mean.

<!-- components/ProductListing.vue -->

<template>

<div class="ProductListing">

<ProductListingFilter />

<ul class="ProductListing__listing">

<li v-for="product in products">

<!-- ... -->

</li>

</ul>

<ProductListingPagination />

</div>

</template>

<script>

import { fetch } from '../services/product';

// ...

export default {

// ...

created() {

this.fetch();

},

methods: {

fetch(options) {

const { data } = await fetch(options);

this.products = data;

},

},

// ...

};

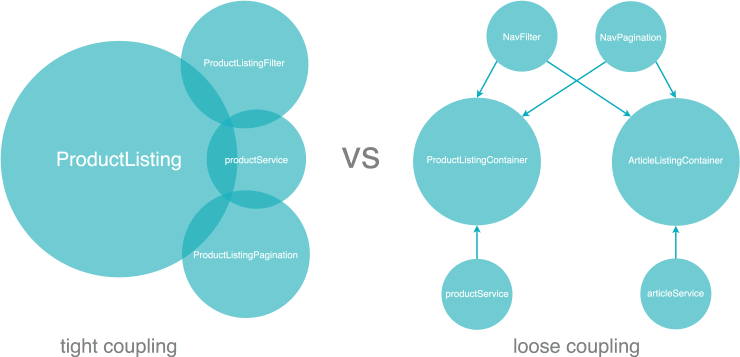

</script>In the this example, the ProductListing component itself fetches the data it needs. This means it’s tightly coupled to the product service. In the following example we use the container component pattern to solve this.

<!-- components/ProductListingContainer.vue -->

<template>

<ListingLayout>

<NavFilter slot="filter" :filters="filters" @click="fetch" />

<EntityList slot="list" :entities="products" />

<NavPagination

slot="pagination"

:page="page"

:page-count="pageCount"

@change-page="fetch"

/>

</ListingLayout>

</template>

<script>

import { fetch } from '../services/product';

// ...

export default {

name: 'ProductListingContainer',

// ...

created() {

this.fetch();

},

methods: {

fetch(options) {

const { page, pageCount, data } = await fetch(options);

this.products = data;

this.page = page;

this.pageCount = pageCount;

},

},

// ...

};

</script>The container component above is responsible for assembling all the necessary components and pass in the data they need and additionally listen to events they emit. The generic ListingLayout component is responsible for basic styling and layout of the listing. We successfully decoupled our very specific components and replaced them with highly reusable generic components.

You can see that we could easily reuse the NavFilter, EntityList and NavPagination components because they’re completely decoupled from any data fetching logic. It would be very straightforward to create a new ArticleListingContainer component by simply reusing the components that already exist.

Recommendation: using component composition with slots should be the preferred way of how to decouple components from logic in order to make them reusable.

Plugins

Another possibility to inject functionality into Vue.js applications are plugins.

// main.js

import Vue from "vue";

import * as userService from "../services/user";

import App from "./components/App.vue";

new Vue({

el: "#app",

userService,

render: (h) => h(App),

});// plugins/user-service.js

export default (Vue) => {

Vue.mixin({

beforeCreate() {

const options = this.$options;

if (options.userService) {

this.$userService = options.userService;

} else if (options.parent && options.parent.$userService) {

this.$userService = options.parent.$userService;

}

},

});

};Above you can see the recommended way of how to globally register a variable with a plugin. You might consider to bind $userService directly to Vue.prototype.$userService but this has the downside that you bind it to every instance of Vue which, depending on the situation, might or might not be what you want. Next you can see how to use the now globally available $userService.

<!-- components/UserFormContainer.vue -->

<template>

<UserForm @submit="login" />

</template>

<script>

import UserForm from "./UserForm.vue";

export default {

name: "UserFormContainer",

// ...

methods: {

async login(data) {

this.success = await this.$userService.login(data);

},

},

// ...

};

</script>Plugins are useful, in the same way as hammers are useful. They are a powerful tool in the toolbox of any Vue.js developer. But with great power comes great responsibility. And as we all know: if the only tool we’re familiar with is a hammer, everything looks like a nail.

Making the $userService globally available makes it very easy to use it everywhere you want. Sounds great? Not so much in my ears. Let’s see why this pattern can be problematic. First, it promotes tight coupling in components that ideally should not be tightly coupled to an API service or some other function that causes side effects. But it’s just so easy to do that with a variable which is globally available everywhere in your application.

Another concern is that it’s not immediately obvious where $userService is coming from, it’s just there. But you can compensate that by keeping a 1:1 mapping of plugin names to the global variable name (e.g. user-service.js -> $userService).

Furthermore, because of the global nature of plugins, there might arise namespacing issues. This may not look like a big deal at the beginning of a project, but once a lot of people are working on the same code, it could quickly become a very real problem.

This pattern is best used for high level functionality which is global in its nature. Vue Router might come into mind for a typical use case. But also with official plugins like Vuex and Vue Router I personally do not love this pattern because it often leads me to building tightly coupled components which are hard to reuse.

Recommendation: use custom plugins sparingly. Additionally you should absolutely avoid accessing global variables from within base components and other mostly presentational components.

Provide / inject

UPDATE: with the Vue 3 Composition API, we are now able to inject dependencies using the Context Provider Pattern automatically.

I feel provide / inject has kind of a bad reputation in the Vue.js world. Unjustified, in my view. I guess one of the reasons why that is, is because variables provided to child components that way are not reactive. But thats a plus in my books. If they were reactive, this feature would be abused to break the one way data flow pattern Vue.js enforces. Another reason might be that in the official Vue.js documentation it is recommended to not use this pattern in generic application code. Unfortunately, it is not stated why this is so, because in my opinion you can do much worse things with plugins.

But the way we want to use provide / inject, we don’t care about reactivity at all: we want to inject dependencies, like the product service we’ve seen earlier, to child components.

<!-- components/ListingContainer.vue -->

<template>

<ListingLayout>

<NavFilter slot="filter" :filters="filters" @click="fetch" />

<EntityList slot="list" :entities="entities" />

<NavPagination

slot="pagination"

:page="page"

:page-count="pageCount"

@change-page="fetch"

/>

</ListingLayout>

</template>

<script>

export default {

name: 'ListingContainer',

inject: { fetchEntities: 'fetch' },

created() {

this.fetch();

},

methods: {

fetch(options) {

const { page, pageCount, data } = await this.fetchEntities(options);

this.products = data;

this.page = page;

this.pageCount = pageCount;

},

},

// ...

};

</script>Above you can see the ListingContainer component which is a generic version of the ProductListingContainer from an earlier example. By injecting the fetch() method we can reuse the component for every content type we like.

<!-- components/ProductListingProvider.vue -->

<template>

<ListingContainer />

</template>

<script>

import { fetch } from "../services/product";

// ...

export default {

name: "ProductListingProvider",

provide: { fetch },

};

</script>If you would like to learn more about this approach, you can take a look at my follow-up article: The IoC Container Pattern with Vue.

The ProductListingProvider is responsible for providing the correct fetch() method to its children. In this example we could’ve used properties as well, but I find it cleaner to use provide / inject for passing functions to child components.

This pattern solves a couple of problems we’ve faced with using plugins. First of all it’s more obvious where a certain method is coming from because we have to reference it in the inject section of our consumer component.

Although it might not seem like a big deal, but having to explicitly inject dependencies in consumer components forces you to think about it more closely which might lead you to decide that a certain component should not be able to trigger side effects.

Furthermore it makes it a lot easier to deal with namespacing issues. When using inject we can also use the object syntax to rename injected properties.

export default {

// ...

inject: { fetchEntities: "fetch" },

// ...

};Recommendation: use this pattern instead of plugins whenever it’s suitable but also don’t overuse it. If you catch yourself using this pattern to pass down dependencies over multiple levels a lot, there might be a problem with your overall architecture.

Functional component factories

Another way to deal with dependency injection in Vue.js is to use functional component factories. I’ve written a separate, in-depth article on this topic.

Do you want to learn more about advanced Vue.js techniques?

Register for the Newsletter of my upcoming book: Advanced Vue.js Application Architecture.

Injecting global state

If you’re interested in how to deal with global state, you can read my article about how to decide when to use Vuex, or some alternative solution for handling global state.

Third party tools

Even though, as we have seen, Vue.js offers a lot of ways to inject dependencies into components, there are also some additional third-party tools. One of the most notable is vue-inject. Most of its functionality can also be achieved by using one of the methods above but additionally this package makes it possible to inject component constructors. There might be situations where this is preferable instead of using slots which only makes it possible to inject component instances.

Wrapping it up

As we’ve seen, there are a lot of ways of how to deal with dependency injection in Vue.js applications. Although I certainly have some strong opinions about various practices, it should be stated that there is no one true way of how to do this. Depending on the type of the application you build, and also depending on your personal preferences, you might use the one or the other approach.

My goal with this article is to extend the available tools in your and my toolbox so the next time we face a Phillips-head screw problem we don’t immediately reach for our good old hammer and start hammering away.